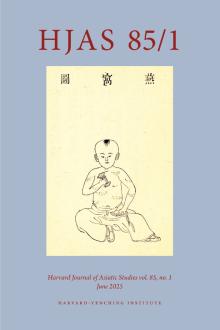

The figure depicted on the cover of HJAS is of a young Chinese male whose body is riven with papules and pustules caused by smallpox. Smallpox is a serious viral disease caused by the variola (Latin for “pustule” or “pox”) virus that begins with symptoms that include fever, tiredness, headache, fever, chills, and nausea. After those symptoms subside, characteristic spots appear on the face, arms, chest, and back that form into blisters and become scabs that can cause disfiguration. In most cases, however, contracting smallpox was a death sentence due to its high mortality rate.

The origins of smallpox are difficult to determine, but in the pre-modern period—as the world increasingly became more connected through migration—smallpox epidemics broke out in many different parts of the world, resulting in what the French historian Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie has called “the unification of the globe by disease.”1 In Asia, smallpox was known in China from an early period (sixth century) and then spread to Korea and Japan (eighth century). By the sixteenth century, the Chinese had developed a medical technique called “variolation” (chuimiao 吹苗; zhimiao 窒苗), a precursor to later vaccination, whereby small amounts of material from smallpox sores were purposefully introduced into healthy people—usually by putting scabs, in either wet or dry form, into the noses of the uninfected (bimiao 鼻苗) or by having the subject wear clothes of a patient who had contracted the disease (yimiao 衣苗)—to infect them, making the resulting illness less severe. In 1796, the English physician Edward Jenner (1749–1823) developed a smallpox vaccine using material from a pustule on a bovine to inoculate patients, providing them with immunity to smallpox. After an initial period of suspicion and resistance to Jenner’s method, the spread of vaccination led to the elimination of smallpox in Japan and Korea in the 1950s, China in the 1960s, and worldwide by 1980. While smallpox is now the only human disease to have been deliberately eradicated, thanks to an aggressive global vaccination campaign, we need to be reminded that in the premodern period it was a deadly scourge that killed hundreds of millions of people. Smallpox did not discriminate, killing the poor and destitute as well as emperors and kings.2 There was no vaccination or cure for smallpox in the premodern period, but in Asia people experimented with numerous techniques to ward off and treat the disease that continued well into the modern period, even after the introduction of Jenner’s vaccination method.

Prior to the arrival of the modern vaccine, epidemic diseases like smallpox were blamed on malevolent spirits, and traditional magico-therapeutic rituals were used to appease them. In Japan, for example, diseases—particularly diseases of epidemic proportion like measles and smallpox—were believed to have been caused by external demonic interventions by “disease-divinities” (ekijin 疫神).3 Shrines and temples dedicated to smallpox deities distributed protective spells and amulets that claimed to protect against smallpox. They also sponsored rituals, goryō-e 御霊会 (departed spirits rituals), to deal with epidemics caused by smallpox, leprosy, and tuberculosis. In premodern Japan, a number of sites were known to produce amulets made from willow branches formed into a pentagonal star (goryōsei 五稜星) that had the power to fend off diseases caused by malevolent spirits (goryō 御霊). The amulets attained their power though linguistic connections between the two homophonous terms.4

One noteworthy place connected with warding off smallpox is the Gion cultic site in Kyoto. Today it is commonly known as the Yasaka 八坂 Shrine, but formerly (until 1868) it was a shrine-temple complex. Gion is closely connected to the famous annual Gion Festival (Gion Matsuri 祇園祭), which began in the ninth century as a goryōe to ward off epidemics caused by disease divinities. It is also the main site of a cult to Gozu Tennō 牛頭天王, an ox-headed disease divinity. Intriguingly, Gozu Tennō, the bovine deity responsible for regularly inflicting smallpox on the Japanese, came to be transformed into a deity said to ward off smallpox. Whatever the logic behind such an association, who could have suspected that centuries later Jenner would develop his smallpox vaccine by extracting material from the lesions on an infected bovine?5

Other methods developed to ward off smallpox came about through linguistic associations and analogical connections. Smallpox pustules or boils are, for instance, referred to in Japanese with the term kasa 瘡, which is homophonous with the word for “straw hat” (kasa 笠). Based on this connection, children were directed to wear straw hats to ward off the disease.6 Connections were also established based on the visual appearance of smallpox pustules that manifested as red marks on the skin. The color red came to be associated with apotropaic powers to repel smallpox spirits, leading people to dress in red, put up red paper prints (hōsō-e 疱瘡絵), and experiment with “erythrotherapy,” or the treatment of smallpox with a red light.7 Although smallpox went by many names, such as hōsō 疱瘡 and tōsō 痘瘡, bean-shaped smallpox lesions were also called “pea and bean pustules” (endōsō豌豆瘡).8 The associations with the pustule’s red bean shape help us to also better understand the folk practice of offering red-bean soup to placate the god of smallpox.9

While the Japanese pursued magico-therapeutic connections between smallpox, bovines, and beans, the Chinese made different associations. We can now return to the image on the cover of HJAS, which is labeled “Bird’s nest illustration” (Yanwo tu 燕窩圖). As Meng Zhang describes in her article “Knowing Exotica: Edible Bird’s Nest and the Cultures of Knowledge in Early Modern China” in this issue of HJAS, the image comes from an edition of Wu Qian’s 吳謙 (fl. 1736–1743) Imperially Compiled Golden Mirror of the Medical Tradition (Yuzuan yizong jinjian 御纂醫宗金鑑; hereafter Golden Mirror), dated 1742 (with a preface dated to 1739), that is in the Harvard-Yenching Library.10 The Golden Mirror dedicates four chapters to smallpox (juan 卷 56–59) and one chapter (juan 60) to different forms of variolation. That smallpox occupied such a substantial part of the Golden Mirror attests to the interest the Manchu rulers who commissioned the work had in knowing as much as possible about the etiology of the disease and its diverse symptoms.11

The chapters on smallpox in the Golden Mirror include about forty illustrations of children whose skin is marked with different patterns of smallpox pustules. The text accompanying the “Bird’s nest illustration,” for example, explains the name by noting how the shape of the smallpox “pustules are clustered like a swiftlet’s nest, interwoven and delicate, they do not form into distinct grain [shapes].”12 Based on various understandings of the natural world and evolving medical conceptions, a relationship was established between smallpox pustules and the nests of swiftlets (Aerodramus fuciphagus). Their nests, found in caves in Southeast Asia, are formed by saliva emitted from their beaks that hardens as it dries. The term “bird’s nest” (yanwo 燕窩) was then linked by analogy and a set of linguistic correlations to magico-therapeutic powers that were perceived to be effective in treating smallpox symptoms also called “yanwo” due to the distinctive patterns of those types of skin lesions.

How the use of bird’s nest as an ingredient in Chinese materia medica transformed into the prized ingredient in bird’s-nest soup, one of the most expensive forms of Chinese cuisine (which today is still believed to have healing properties, such as replenishing one’s depleted energy), is a story that can be savored in Zhang Meng’s essay in this issue. HJAS thanks the Harvard-Yenching Library for its permission to reproduce the image.

- Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie, The Mind and Method of the Historian, trans. Siân Reynolds and Ben Reynolds (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1981), esp. chap. 2. Originally published as Le territoire de l’historien, vol. 2 (Paris: Editions Gallimard, 1978). See also William McNeill, Plagues and Peoples (Garden City, NY: Anchor Press, 1976).

- For a general history of smallpox and its eradication, see Donald R. Hopkins, Princes and Peasants: Smallpox in History (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002).

- Yamamoto Hiroko 山本ひろ子, Ishin: Chūsei Nihon no hikyōteki sekai 異神: 中世日 本の秘教的世界 (Tokyo: Heibonsha, 1998), pp. 11–14

- McMullin, “On Placating the Gods,” p. 275.

- This mysterious connection has also been pointed out in McMullin, “On Placating the Gods,” p. 293.

- Hartmut O. Rotermund, “Demonic Affliction or Contagious Disease? Changing Perceptions of Smallpox in the Late Edo Period,” Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 28.3–4 (2001), p. 378.

- Hartmut O. Rotermund, Hôsôgami ou la petite vérole aisément: Matériaux pour l’étude des épidemies dans le Japon des XVIIIe, XIXe siècles (Paris: Maisonneuve et Larose, 1991).

- Jannetta, Epidemics and Mortality, pp. 65–66.

- Claude Lévi-Strauss, The View from Afar (New York: Basic Books, 1985), p. 194.

- Wu Qian, ed., Yuzuan yizong jinjian, 91 vols. [90 juan plus 1 suppl.] ([n.p.]: Neifu, 1742, with preface dated 1739); No. T79107388, Harvard-Yenching Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, https://listview.lib.harvard.edu/lists/drs-54030877.

- Marta Hanson, “The Golden Mirror in the Imperial Court of the Qianlong Emperor, 1739–1742,” Early Science and Medicine 8.2 (2003), p. 139.

- 痘形累累似燕窝, 聯繫细密不成顆; Wu, Yuzuan yizong jinjian, v. 58 [j. 57], p. 34b (seq. 46), https://iiif.lib.harvard.edu/manifests/view/drs:430543363$46i.